As reported earlier, last year, the Ukrainian central bank — the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) —conducted a public consultation on a draft law on financial services (available in Ukrainian). The Ukrainian Parliament received this on 15 February 2021 (available in Ukrainian). The current regulatory framework was adopted in 2001 and the draft law aims to replace it with a set of refreshed rules addressing present day challenges. The following is a summary of certain special features of the draft law compared with the current regime.

Architecture of the financial services market

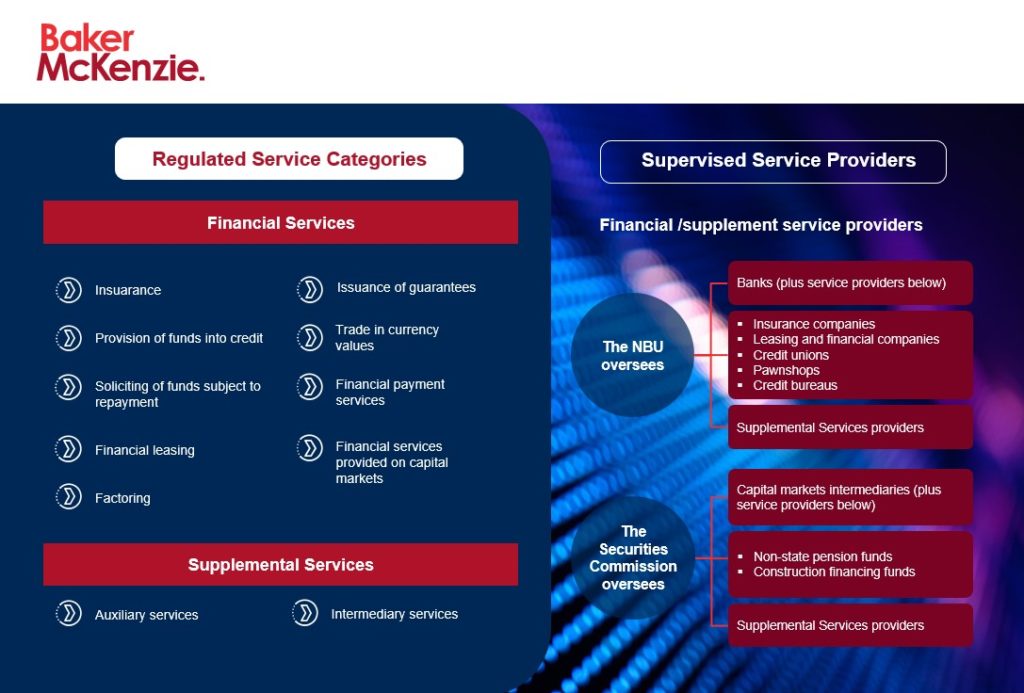

It is contemplated that the draft law will cover a number of financial and supplemental services, most of which match those currently regulated. The key difference is that the draft contemplates the regulation of categories of financial services rather than specific services. Hence, the regulatory framework will become more flexible because, under current rules, it is prohibited to carry out an activity that is not specifically listed in the law.

You may note the allocation of responsibilities between the two competent authorities vis-a-vis the various types of financial services providers. Historically, three different regulators supervised this sector. Starting from 1 July 2020, the Financial Services Commission ceased to exist. Therefore, the remaining two regulators, the NBU and the Securities Commission have shared oversight of those entities previously overseen by the now defunct regulator.

How do Ukraine’s licensing requirements apply to cross-border business into Ukraine?

The draft law as originally proposed by the NBU last year explicitly touched on cross-border business. In particular, it contained a general rule that a foreign financial institution or a legal entity authorized to provide financial service(s) under a foreign law would be able to do so in Ukraine pursuant to the requirements of: (i) the special law(s) applicable to such activity; and (ii) secondary legislation adopted by the competent authority.

Unfortunately, the revised text of the draft law now before the Ukrainian Parliament does not reflect this position. At the same time, it contains provisions that infer the possibility of authorizing such cross-border services. This is because each competent authority is authorized to oversee the activity of foreign service providers active in Ukraine and to collaborate with the responsible foreign regulators. In view of this, any financial services proposed on a cross-border basis may need to be reviewed on a case-by-case basis to identify whether they would be in line with the general requirements and criteria of any special law applicable concerning the intended service.

Noteworthy novelties of the Draft Law

- Risk-based approach

The draft law contemplates that the competent authorities will be able to allocate more resources to higher risk categories and adopt and enforce either a heavier or a “light touch” set of rules accordingly. Thus, the draft law indicates that the relevant competent authority will be authorized to adopt criteria to define: (i) the risk profile of the respective financial/supplement service provider; and (ii) respective oversight actions vis-a-vis the same.

- Professional opinion of a competent authority

The draft law envisages that a competent authority may apply a so-called “professional opinion” when carrying out its functions. Apparently, this refers to a case when the competent authority deals with non-routine matters subject to a more comprehensive assessment. It is noteworthy that professional opinions will be issued in the form of an official document and the respective market participant will be able to challenge the opinion within 15 business days of receipt. Moreover, any loss caused to the service provider as a result of such a professional opinion may be eligible for compensation.

- Financial secrecy

The draft law aims to resolve one of the legacy issues in the financial services market and defines all client and third-party data handled by intermediaries as “financial secrets,” although data handled by banks will remain governed by the rules applicable to “banking secrecy.” This will hopefully resolve current legal uncertainty, whereby there are different piecemeal rules defining the rules for privileged data handled by the service providers. It is not always straightforward to identify which item of data falls into which regime. It is curious that the draft law does not envisage a general disclosure regime for such data by the relevant service provider, but rather by the competent authority (except for a few use cases, such as disclosure to: (i) a third-party contractor; or (ii) based on the consent of the data controller). Moreover, it appears that the draft law’s provisions may override any conflicting disclosure provisions in other legislation. The practical implication of this may be that such disclosures may face difficulties in certain cases when not specifically addressed in the law.

- Outsourcing

The draft law has substantially changed the approach to outsourcing compared to what was proposed at the public consultation stage. In particular, it previously defined “outsourcing” as a transfer of processes to a third party based on a contract with a view to optimize both the cost and processes of a service provider. The revised version has removed the reference to the above condition and it indicates that any performance by a third party of a process or function of a service provider would qualify as “outsourcing.” That said, the competent authority will be able to define the criteria that potential outsourcing providers will be required to meet.

The revised draft also changes the approach toward permitted outsourcing. It originally indicated that special laws (and secondary legislation) would contain a list of such activities. Now, it contains a general rule that both this law and special laws should provide for a list of functions (or processes within functions) that may be outsourced. However, currently, the draft law provides such a list only for financial services providers regarded as “financial companies” and “pawn shops,” which do not include banks, insurance companies, credit unions and capital markets intermediaries. Moreover, the draft law provides for a rather narrow list of processes (functions) that may be outsourced. In particular, it only includes “accounting,” “internal audit,” “risk management” and/or “compliance function.” This is also subject to a “financial company” and “pawn shop” not being regarded as an “enterprise with a social interest.”

Given all this, it appears that the draft law provisions on outsourcing lack substance and may need to be updated: (i) to enable the financial services industry to benefit from the existing opportunities in the outsourcing industry; and (ii) to make these opportunities available to all financial services providers in Ukraine.